That’s right: Wikimedia DC is hiring for a five-month contract position to manage the Wikipedia Summer of Monuments program. Summer of Monuments is an outreach campaign modeled off of Wiki Loves Monuments, a photography contest successfully carried out in the United States in 2012 and 2013. The goal of Wiki Loves Monuments was to get pictures of historic sites, recognized on the National Register of Historic Places. Two years of contests resulted in 30,000 pictures uploaded, enhancing Wikipedia’s coverage of these historic places. We got the idea for Summer of Monuments after seeing that despite two years of these contests, the contest benefits some parts of the country more than others. That is to say, 30,000 uploads later, there are still states where fewer than 50% of the registered historic sites have pictures on Wikipedia.

Most of these states are in the South, including Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas, North Carolina, Mississippi, Missouri, Kentucky, Georgia, Tennessee, and Louisiana. To get the pictures of the sites we need, we will carry out a campaign that involves reaching out to county historical societies, individual photographers, and contributors on Wikipedia. The campaign will extend nationwide in September, comparable to the Wiki Loves Monuments contest held over the past two years. Your job will be to help develop and execute this campaign, supplementing the efforts of an enthusiastic online community.

Job description:

Wikimedia DC is looking for a project manager to run its Wikipedia Summer of Monuments campaign in 2014. This will be a paid contract position that will begin in May and end in mid-October. This position is based in Washington, DC, but some travel (with expenses paid) will be required as part of the job.

Duties:

- Outreach to county historical societies and individual volunteers to contribute photographers

- Coordination with WikiProject NRHP

Requirements:

- 1–2 years project management or field organizing experience

- Excellent interpersonal and collaboration skills, a demonstrated aptitude for building professional relationships, including through online communications

- Strong organizing skills, capable of operating with little direct supervision

- Must provide own laptop computer

Preferred, but not required:

- Strong preference for candidates with experience on Wikimedia projects, including Wikipedia

- Regardless of Wikimedia experience, an ability to categorize photographs according to a set of standard criteria

- Photography experience, owning a professional-grade camera

- A strong sense of logistics and the ability to interpret visual data (namely maps) would be helpful

- Demonstrated interest in history and historic places

- Existing relationships with historical societies, particularly in the Southern United States

To apply:

To apply for the position, please e-mail a cover letter and résumé to James Hare at [email protected]. We will contact you if we are interested in further consideration of your application. No phone calls, please.

More information:

- About Wikimedia DC

- Wikimedia Foundation grant proposal funding the program, including the job position

- Wikipedia article on Wiki Loves Monuments

- Progress report maintained by WikiProject NRHP

- Press release announcing the results of Wiki Loves Monuments 2013.

Reference books in the Library of Congress

We are very pleased to announce our upcoming edit-a-thon at the Library of Congress on Friday, April 11, the first event we have had with the Library since the Google Opening Reception of Wikimania 2012 nearly two years ago. We think it is only fitting that the world’s largest encyclopedia would partner up with the world’s largest library.

Our event will focus on the Africa Reading Room, which includes books on African and Middle Eastern history. We have selected this—out of all of our options—because we are in a position to address a long-standing issue on Wikipedia. There has been much press coverage of Wikipedia’s gender gap, resulting in an encyclopedia that reflects the prerogatives of its overwhelmingly male authorship. This means there are more articles about men than women, to such an extent that some incredibly accomplished women go years without having articles on Wikipedia.

That is only part of the systemic bias equation. Wikipedia also has a Western bias with regards to what is written about. Statistics collected by WikiProjects, which are informal groups of Wikipedia editors, provide evidence of this problem. WikiProject Africa reports that there are 57,753 articles regarding Africa on Wikipedia, while WikiProject United States reports that there are 227,878 articles on topics relating to the United States. To give some perspective on this, the United States is just one country, hosting 4% of the world’s population, while Africa is a large, diverse continent with 54 countries and over one billion people.

This is obviously lopsided, so we need your help. To help, meet us at 9 AM on Friday, April 11 in the lobby of the Madison Building. Use the entrance on C Street, by the Capitol South Metro station. You will need to check your coat in the cloakroom; personal items you wish to bring with you must be transported in a clear plastic bag. If you do not already have a Library of Congress researcher card you will need to get one before proceeding to the Africa Reading Room. We will be editing from 10 AM to 1 PM. If you are new to Wikipedia we will be more than happy to help you get started—everyone’s a newcomer at first! After 1 PM, you will be able to get lunch at the Library’s cafeteria and stay for as long as you would like.

In the long term, we would like to see Wikipedia editors continue to use the Library of Congress as a resource for improving Wikipedia, whether independently or during future Wikimedia DC events. We would also like to build a brain trust of people who are interested in Africa and are eager to do their part to improve Wikipedia. To sign up for this upcoming event, check out our event page on Wikipedia. If you cannot come Friday the 11th but wish to still help, send an email to kristin.anderson [at] wikimediadc [dot] org.

We hope to see you at the Library!

]]>

Dominic McDevitt-Parks. Photo by Benoit Rochon

As announced today on the blog of the Archivist of the United States, our cultural partnerships coordinator Dominic McDevitt-Parks will be re-joining the National Archives and Records Administration as a full-time employee in their Office of Innovation. He originally served as their part-time Wikipedian in Residence back in 2011, and as the first-ever permanent Wikipedia liaison for a cultural institution, he will be continuing the work he started for them.

Wikimedia DC and the National Archives go back years. We hosted Wikipedia’s tenth birthday celebration at the Archives back in 2011, and our community has worked closely with them to make their content available to the Wikimedia projects. Dominic’s efforts at the Archives led to over 100,000 digital scans from the Archives to be uploaded to Wikimedia Commons, as well as multiple scan-a-thon events, and Wikimedia DC looks forward to continue working with them.

Congratulations, Dominic, on your new job!

Wiki Loves Monuments Update

So far, over 5,300 images have been uploaded as part of Wiki Loves Monuments! If you have a picture of a site on the National Register of Historic Places to upload, follow the instructions here to upload. You can also use our handy map tool to find a place that still needs a picture. Check it out—there may be a site just steps from where you live or work! Remember, you have until September 30 to upload your picture in order to qualify for our contest.

Don’t forget that this Saturday we have twin photo walks in Baltimore and Richmond. We hope to see you then!

]]>

Participants at GLAM Boot Camp in Washington, D.C.

Recently, Wikimedia DC held GLAM Boot Camp, a new type of event which we hope will be repeated by others in the Wikimedia movement. The most basic aim of GLAM Boot Camp was to attempt to build the skills and capacity for the Wikimedia movement. It took place from April 26–28 in a conference room at the U.S. National Archives with 12 main attendees made up of experienced Wikimedia editors. The intensive, three-day workshop, hosted by myself and Lori Byrd Phillips, featured a mix of expert presentations, group discussions, breakout sessions, and hands-on tutorials. We were lucky enough that one of the Wikimedians in attendance wrote about the event in The Signpost, English Wikipedia’s newsletter, which gives a good recap of GLAM Boot Camp from a participant’s point of view.

The idea for a “boot camp”-type event was first proposed and developed at GLAMcamp London by members of the global Wikimedia community in September 2012. You can see our original notes from GLAMcamp here. We identified that, particularly in the United States, our main efforts had always been directed at reaching out to and winning over cultural institutions, but now we face a lack of online and real-world volunteers ready to meet the growing demand of institutions interested in contributing in some way to Wikimedia. Many potential projects have stalled not because of lack of cooperation, but because of lack of involvement by the Wikimedia community. Institutions do not yet have the expertise in Wikipedia to become Wikimedians on their own. Our largest bottleneck in GLAM-Wiki, therefore, is capacity. The stated, ambitious goal of the first GLAM Boot Camp was to broaden the participation of the general Wikimedia community in the GLAM-Wiki movement by inviting and training key Wikimedians. I think that we were successful in taking a big step towards that goal. Another goal was to establish a model for future similar events, and I hope that as we work on our documentation, others will be able to use our experiences to guide them in making another GLAM Boot Camp elsewhere.

All of us who have been to events like GLAMcamp or Wikimania know that oftentimes the most important part is not the structured sessions, but just being with a group people for a couple of days and sharing perspectives—even over coffee or back at the hostel. The main takeaways for me at these events were about the attendees. The fact that we fully funded all attendees from across the U.S. and Canada was integral to ensuring we were able to recruit new participants. Second, we specifically invited the people we thought would be key, rather than hoping people would sign up. This ended up making even more sense in retrospect, because we were so happy with who came, but if the idea was to reach people who were not normally part of GLAM-Wiki projects, we were trying to reach people who wouldn’t already be following our normal channels of communication and who would not inclined to sign up, even if they heard about it or were familiar with the goals of GLAM-Wiki. The geographic diversity of the participants we invited allowed us to hold an event with a variety of online experiences, and to provide Wikimedians who may not have been able to attend a meetup before to get to meet other Wikimedians face-to-face.

As co-organizer, I want to tease out a few more important points:

Attendees

We posted a list of attendees to the page; the names in green were those who we invited as full participants for the entire event. Of these, only about three had actually signed up or registered interest before we started sending out invitations. For the others, I spent hours looking for people; asking for opinions of others; and looking through user contributions of people who had participated in any GLAM WikiProjects online, in meetups, or in any of various other Wikimedia activities or subcommunities (such as administrators and featured content writers). Participants came from all over the United States (New York; Maryland; Los Angeles; San Francisco; Portland, Ore.; Philadelphia; Kansas; Michigan; and Chicago) and Canada (Halifax, Vancouver, and Winnipeg). No two people were from the same metropolitan area, and most came from areas without regular Wikipedia-related events. For many, this was their first time at a Wikipedia event of any kind. The size of the group, 12 invited attendees with no more than five organizers and guests, was the perfect amount to allow for productive discussions.

Program

We designed a program that was very unlike GLAMcamp and a lot more structured than most unconferences, but with more practical sessions than a traditional conference. It was something between a Wikipedia Academy, where newcomers are taught how to edit Wikipedia, and a campus ambassador training. You can see our program here. We generally moved from presentation-heavy to discussion-heavy sessions. The first day was our high-level overview of, and introduction to, cultural institutions and the history and present circumstances of GLAM-Wiki. Michael Edson’s inspiring opening talk was to give participants an insider perspective of cultural institutions, and we talked a lot about institutional missions and how to connect the work of Wikimedia with that of cultural institutions. The second day we moved into more practical matters, going through the whole “lifecycle” of a Wikimedia project, and talking about specific events and projects. By the third day, we spent more time in discussion, getting the boot campers to articulate their own visions of GLAM-Wiki and how they personally could contribute to it. We ended up having unplanned breakout sessions a couple of times because attendees were excited with ideas as we showed them things like our one-page guide that needed improvement. If you would like to dig into the Etherpad notes from each day, they are listed at the top of the program, linked above.

Logistics

The event was possible for us in the U.S. because logistics and funding were largely handled by James Hare and Wikimedia DC, which budgeted $8,000 for the conference from its program budget. Most of the money went towards funding the travel and accommodations of the attendees. All attendees were fully funded, and this was crucial. Most of the travelers had their flights booked by Wikimedia DC and stayed in a hostel (same as the one used for Wikimania 2012 and GLAMcamp DC). Wikimedia DC also hosted two dinners and provided refreshments throughout the day.

Speakers

The ambitious nature of the workshop, with three full days of programming, meant Lori and I spoke a lot. We broke things up a little by inviting special speakers in certain topic areas, often where they had as much or more expertise as either of us did. Some of these speakers were locals from the DC area that agreed to come in, and some were attendees we invited to present to the group on something they are skilled at. Examples include the Wikisource and Commons workshops, a session on event planning, and a session on grants and chapters. We also led off with special guests: Archivist of the United States David Ferriero gave a welcome address, and Michael Edson, who had just returned from keynoting GLAM-Wiki London, gave an epic talk for most of the first morning. At least half of the sessions were led by Lori or I, though, and future GLAM Boot Camps probably would want to find ways not to give so much work to two individuals, for their own sanity.

Venue

The venue was provided by the U.S. National Archives, though there were pros and cons for this. The main pro was that there was no cost associated with securing a venue! We might have been able to find a room elsewhere without a cost, but 3 days, all day for no cost is a big ask. The other main benefit was that we were in a good location and were able to take advantage of having David Ferriero make appearances. We did face typical problems with working with a bureaucratic venue, like catering and security all taking more time than we wanted.

Outcomes

For me, the most important outcome was seeing attendees who were all not the same old faces come in, eager to get involved. Gradually, they took more ownership and responsibility for GLAM-Wiki, as they began to feel more empowered and a part of the effort. There were practical outcomes, like specific documentation or project pages to improve. More than that, though, most attendees came away intent on contacting local institutions or organizing their local Wikipedia community. I am as excited by the overall community-building I think we did around GLAM-Wiki, which will help it be more successful as it is more accepted and integrated with the Wikipedia community, as I am by any specific skills attendees may have learned or GLAM projects they may go off and start.

The need to reach out more to the Wikimedia community, as much as to cultural institutions, is something I feel very strongly about, so I am so glad we were able to hold this event, and grateful to everyone who made it possible and attended.

]]>

Dominic McDevitt-Parks during Campus Ambassador training

GLAM, the Wikimedian acronym for Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums, equates to more than just the institutions categorized by the letters. It also encompasses the merging of communities. On August 13, 2012, Dominic McDevitt-Parks, the wikipedian-in-residence at the National Archives and Records Administration since May 2011, gave a talk labeled “Cultural Institutions and Wikipedia: a Mutually Beneficial Relationship” on what a symbiotic relationship between Wikipedia and a cultural institution can look like.

Introducing Dominic was Wikimedia DC’s own Kristin Anderson, who described the Wikipedian community to the Library of Congress audience as “the only people who like information as much as library catalogers are Wikipedians…Wikipedia and the Library of Congress share Thomas Jefferson’s dream of…information for everyone.”

In his talk, Dominic broke down how cultural institutions and Wikipedia can work together to form mutually beneficial partnerships. If the goal of an institution is to encourage the use of its materials, Wikipedia is a natural fit, being the 5th largest internet site. Dominic gave numbers and a visual to put it all into perspective. The National Archives website gets 17 million views a day. In contrast, a very conservative estimate of the number of views that the Wikipedia articles that use National Archives material receive every day is well over a hundred million. This isn’t pointing at a problem, but at a fact, and one that can lead to a solution for many institutions; Wikipedia provides a ready-made platform to spread not only information through articles, but also to put up source documents on sister projects Wikisource and Wikimedia Commons.

The National Archives takes full advantage of this online volunteer community by encouraging local Wikipedians to come to scan-a-thons and the online Wikipedian community to tag the uploaded scans and transcribe the text documents on WikiSource. Due to the tireless efforts of many Wikipedians, well over a hundred thousand documents have been scanned in and transcribed.

Even if the question of whether or not Wikipedia is a reliable source is raised, if a person sees a mistake on Wikipedia, it is up to him or her to make the change. Unlike other encyclopedias or collections, if people find a mistake on Wikipedia or one of its sister projects, they can correct it. There is a large community of editors watching to make sure the information is as accurate as possible. Recognizing that its own information is not infallible, the Archives has created a feedback page on its own website for people to post mistakes and corrections on.

Dominic summarized the role of a Wikipedian-in-residence nicely: the Wikipedian-in-residence provides access to the institution to the Wikipedia community and vice versa, which brings about not only community engagement, but also culture change within the institution itself, making it more open and accessible to the layperson. This is change which the National Archivist David Ferriero heartily embraces and encourages, in the words of one blogger during the National Archives ExtravaSCANza in 2011, “If it’s good enough for the National Archivist, it’s good enough for you.”

Lisa Marrs, Outreach & Program Coordination, Wikimedia DC

]]>

Editing away in the Luce Center

Sculptures dot the hallways and rooms alongside works of art representing more than 7,000 artists in the National Historic Landmark, the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Within the many-tiered Luce Center 15 people gathered; their quest, to embark upon an edit-a-thon focused on 30 different masterpieces hand picked by the museum Director, Elizabeth Broun. Before the program began, she spoke to everyone about how putting the museum’s art on Wikipedia is one of her overarching “subversive goals”.

Following a tour and a scrumptious lunch provided by the museum, everyone filed into the Luce Center conference room and started working. Many participants had never edited Wikipedia, but it wasn’t long before they whetted their first tooth. From artist Childe Hassam to a created article on the Nakoda Wikipedia everybody contributed something to the world’s largest online encyclopedia.

Georgina Goodlander, the Web and Social Media Manager at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the wonderful lady without whose efforts this event would not have been possible, has now got an appetite for Wikipedia, she says. A definite success, she plans to make Masterpiece Museum a series instead of a one-time event. Some meetings may even take place on a Saturday to catch those who cannot leave work during the week.

To see the images uploaded during the event, click here. To see articles created or improved during the event, click here.

Lisa Marrs, Outreach & Program Coordination, Wikimedia DC

]]>

Charles Street entrance to the Walters Art Museum.

Down Charles Street in Baltimore, Maryland sits a museum basking in the hot summer sun like a contented cat, right across from the gloriously green, statue-populated, and many-fountained grounds of Johns Hopkins University. Within the museum’s cool, white marble halls and rooms rest thousands of art treasures, from ancient American statues to canvasses from the mid-1900s. This is the Walters Art Museum, completely free to the public, and the site of ArtBytes, a hackathon that debuted the weekend of July 27, 2012.

Hackers from as far away as New York came together with museum staff to figure out how to better the museum experience in a competitive, yet collaborative atmosphere. The teams worked through the weekend and most of them arrived at the ending presentations with nearly completed, if still rough, products. There was team Time Machine’s mobile app that could recognize a work of art and then show that work’s original color or an xray of that work depending on the images and information the museum has in storage. Team Pez-Head created a way to do 3D modeling of sculptures and then print them out in rather excellent detail to make art more accessible by making it “touchable”. Both Team Schrodd0n and WalTours made different kinds of maps for mobile devices for the Walters Art Museum to help visitors navigate exhibits. Dave Raynes, a team of one, worked on making the data shored up in the Walters databases more easily available to software, which was a great help to many other groups. Badgify the Walters was all about putting up QR codes around the museum for kids to find and scan to collect points by doing quizzes on the art works which would eventually culminate in collecting badges on a profile online.

Although all groups ‘won’ the competition and each received $500, the judges managed to pick out two favorites to shower $1000 on. The first was

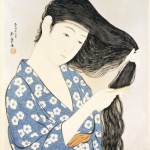

“Put Art in its Frame,” a mobile application where you can choose what time period the exhibit is in and then see all the significant world events that happened during that time period. The second was “Tanzaku,” a mobile application taking from the Japanese idea of writing notes on strips of paper (tanzaku) and hanging them up for all to see, which is an idea already in effect in the Hashiguchi Goyo “Beautiful Women” exhibit, where visitors write their own tanzaku and put them up on wires. The mobile app is a way to leave comments on art pieces and exhibits, as well as on the museum itself, with the potential to be connected to various social networking sites. All of this provides a way to potentially go on a tour with absent friends and explore how various pieces of art have touched different people.

So many amazing projects came out of this hackathon, sprung from the creative minds and intense will of their creators. Tapping into this pool of talented people, the Walters Art Museum ultimately benefited, providing an example other Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums may follow. The museum is not only enterprising in terms of calling forth capable people to use their talents and grow new abilities, but it also furthers its own goals by tapping into existing projects such as Wiki Loves Monuments, an event coming up in September where people all over the globe will sally forth to take pictures of public objects of historic and/or artistic value and upload those pictures onto Wikimedia Commons, both to increase the stock of public domain photos and to enter their photos in a contest. The Walters’ Wiki Loves Monuments is accepting pictures now of public artworks all over Baltimore as an extension of their Public Property exhibit (although note that only pictures submitted to Commons during the month of September are eligible for the worldwide contest).

Lisa Marrs, Outreach & Program Coordination, Wikimedia DC

]]>

Grave of Representative Tom Lantos at the Congressional Cemetery, Washington, DC. Note the QR code.

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license under Peter Ekman.

All the world’s a stage, and every prop, scene, and player conceals a story. On the way to work we pass by some statue or fountain that once tickled the imagination and now sits comfortable and unnoticed in its familiarity, and wonder what story lies behind it. Passing an eccentric neighbor’s cubicle and glancing at the sprinkling of medieval portraits adorning its walls, we briefly wonder just who Nostradamus actually was. With leaps in information technology, finding the answer can be as easy as pointing your smart phone at a little card.

Just in the past year QR codes have cropped up on walls and banners, on brochures and menus, linking customers with the appropriate smart phone application to websites about the advertised business or to nutritional facts on a menu’s dishes. Increasingly, institutions such as museums, galleries, and city governments realize the educational potential behind these codes. Wikipedia, with its crowd-sourced articles on millions of topics in hundreds of languages, is the most comprehensive source for articles about pieces of art or the history of a central park. The love child between these institutions and Wikipedia is QRpedia.

Just recently, the 205-year-old Congressional Cemetery became the world’s largest outdoor encyclopedia of American history. Sixty QR codes link visitors to the Wikipedia pages of such diverse people as Congressman Henry Clay, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, and Leonard Matlovich, America’s first openly gay serviceman. The Wikimedian behind this effort, Peter Ekman, explained why he chose a cemetery, not exactly the typical GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museums) outreach fare.

“It chose me,” he said. “Everything I wanted to do, the cemetery people were happy to oblige. Most of the article compilation work was already done by anonymous Wikipedians so most of the work was just printing out the codes and putting them up. It is cheap, inexpensive, anybody can do this.”

It took $400 to print out the QR codes, laminate them, and obtain the garden stakes to anchor them into the soil.

“Local groups can do this themselves,” Ekman added. “Once it’s been established that it can be done, historical societies and other locally-oriented groups can see that this gets done.”

While QRpedia is relatively new in the US, many places in Europe have already embraced it. A prominent factor in its success in Europe thus far is that, not only does the code take the smart phone user to the Wikipedia article associated with what they are looking at, it also directs them straight to the article in the phone’s set language. Even if a museum or plaque does not provide information in a visitor’s native tongue a QRpedia code can directly circumvent the informational gap.

The most comprehensive QRpedia project is actually an entire city, the city of Monmouth, Wales, and the project is known as Monmouthpedia. Aiming to cover every single notable place, person, artifact, plant, animal and other item of note in Monmouth in as many languages as possible, but with a special focus on Welsh, this project carpets the city with QR codes. Ekman said that he was inspired by the monumental, ongoing achievement of Monmouthpedia, adding that “if they can do it, so can I, and so can anybody else.”

Visit http://qrpedia.org/ to play around and see how extraordinarily easy it is to create QRpedia codes. The most difficult part for volunteers can be obtaining permission to post the codes, but everything else is a breeze.

Lisa Marrs, Outreach & Program Coordination, Wikimedia DC

]]>

The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in downtown DC is more than the cornucopia of book stacks it appears to be from the street. Within its glass walls its librarians in various departments labor tirelessly creating programs for multitudes of patrons. Chris is one such librarian. He works with adaptive services teaching the blind how to use computers. This past year a group of students from his advanced class decided to go one step further. Every month or so they meet as a book club and pick a book that doesn’t have a Wikipedia article yet, listen to it, then return and, using the software Chris teaches them how to use, write an article as a group.

It is an amazing privilege to watch them at work. All of them are older folks and have varying amounts of experience with computers but they all take turns typing sentences, navigating the keyboards, counting keys from left to right to find the right letter and clicking it before searching for the next. Everyone participates in the process of writing and brainstorming content and, in the end, what they create is a new Wikipedia entry, expanding the horizon of shared information just that much further.

Their most recent article is about the book Fallen Grace by Mary Hooper and their next project is Outwitting Trolls. To put it in the words of an attendee, “We may get loud and rambunctious, but we pull through. We always pull through.”

Lisa Marrs, Outreach & Program Coordination, Wikimedia DC

Copyright notes: Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Washington, D.C. by David Monack, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license from Wikimedia Commons.

]]>